From Oil Gushers to Golf Balls: Saudi Aramco Bets on Chemicals

Aramco says $20 billion complex near coast a ‘Game Changer!’ Diversification push is part of crown prince’s post-oil plan

Under a tent in the Saudi desert, Ziad Al-Labban’s showing off his vision for the world’s largest oil supplier—and it looks like an Ikea store.

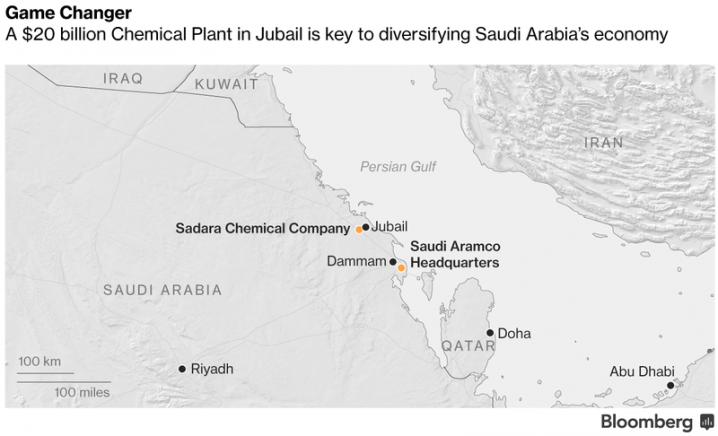

Al-Labban has spent his career helping Saudi Aramco meet about 10 percent of global crude demand, but right now all he wants to talk about are all the petrochemicals used in the modern home he’s replicated at Sadara, the sprawling new $20 billion complex he runs in the industrial hub of Jubail.

The mattress in the bedroom, the plates in the kitchen, even the Chevrolet Caprice in the driveway—he’s too excited reeling off the vast array of products enhanced by his chemicals to notice the scorching heat. At 46 degrees Celsius (115 Fahrenheit), it’s way hotter than most places have ever been.

“Do you see that plasma TV?” Al-Labban asks enthusiastically, pointing to the entertainment center in the model living room. “We will produce the chemical coating that goes into that screen.”

Al-Labban has managed Aramco units before, including in the U.S., but this one is like no other. Sadara, a venture with Dow Chemical Co., emblazons its website with “Game Changer!” for a reason. The facility’s completion is key to the kingdom’s efforts to diversify the economy, develop new industries and create jobs for millions of youth. It’s the largest plant of its kind ever built in a single phase, taking more than 60,000 workers five years to assemble.

Peak production is just weeks away, which is good news for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. With the economy flatlining and the budget strained, he’s put next year’s initial public offering of shares in Saudi Arabian Oil Co., as Aramco’s formally known, at the center of his “Vision 2030” blueprint for life after oil. Some royals expect a $2 trillion valuation, which would let them raise $100 billion by selling just 5 percent, though many analysts expect half that.

Opening up the national cash cow to foreign investors for the first time since it was nationalized in 1980 is a major gamble for the kingdom’s traditionally conservative leaders. They’re betting that spending billions of dollars to become a major chemical player will appeal to potential investors by easing Aramco’s—and thus the country’s—dependence on crude output.

“Our goal is to be a top-tier energy and chemical company by 2030,” Abdulaziz Al-Judaimi, Aramco’s senior vice president of downstream, said in an interview at the company’s headquarters in Dhahran, two hours’ drive south of Sadara.

If all goes as planned, Sadara will crank out multiple tons of the glycol ethers, isocyanates and other chemicals used in everything from golf balls and gum to sofas and soaps. But the ambitions of Aramco, formed when the Saudis signed their first oil concession with U.S. investors in 1933, don’t stop there.

With Sadara up and running, Aramco is drawing up plans for another $20 billion complex, this one with Saudi Basic Industries Corp., or Sabic, until now the dominant chemical company in the country.

“We will expand organically, but we also see inorganic opportunities,” Al-Judaimi said, suggesting a deal-making appetite that’s rare for a company with little experience in mergers and acquisitions. “Chemicals is a global business.”

While the diversification will reduce Aramco’s exposure to volatile energy markets, the sector traditionally delivers low margins and requires know-how the company currently lacks. Its Petro-Rabigh venture on the Red Sea with Japan’s Sumitomo Chemicals Co. Ltd. hasn’t turned a profit in years.

Still, Al-Judaimi, one of Aramco’s top seven executives, said the company can achieve “a significant increase in value per ton if we do chemicals rather than just refined fuels.” He said Aramco and its partners boosted chemical capacity 60 percent last year to 28 million tons. It also created a new subsidiary, yet to be named, to “oversee its rapidly growing chemicals and plastics portfolio,” according to the prospectus for a recent Islamic bond sale.

Drawbacks to the pivot include “increased exposure to a low-margin, low-labor business,” said Jim Krane, a research fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute in Houston. Aramco concedes its chemical investments won’t add that many jobs, but argues that they’ll drive growth in other sectors that will.

Within the oil industry, chemical units have often been marginal to the bottom line, but crude under $50 has changed the calculus for majors like Exxon Mobil Corp., Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Total SA. Producing petrochemicals is usually more profitable when oil prices fall, making the feedstock cheaper. Aramco has never published its accounts, but data from peers show that processing crude into chemicals rather than fuel can earn several extra dollars per barrel.

In 2015, Aramco invested 1.2 billion euros ($1.37 billion) in a 50-50 venture with German group Lanxess AG that makes elastomers, used to make golf balls more bouncy and chewing gum softer. The joint venture, which is active in nine countries, reported 2016 earnings before interest, taxes and amortization of $373 million.

IPO Concerns

For all the hype about capturing extra margin, through, the chemicals push presents significant risks. If the gambit flops, the kingdom would have poured tens of billions of dollars into a low-margin industry that could have been put to work elsewhere. Worse, after the IPO, foreign investors may start demanding the company stick to its core competency—pumping crude.

The expansion is also a tacit acknowledgement that Aramco needs to adapt to the dramatic changes in global energy use that analysts at the International Energy Agency, among many others, see coming. The IEA predicts demand for passenger-vehicle fuel will increase just 0.1 percent a year through 2040, compared with a 1.5 percent annual rise in petrochemical consumption.

“The chemicals business is growing faster than fuels, so investing in chemicals is a way to mitigate the risks of our concentration on oil refining,” Al-Judaimi said. “We see a premium to chemicals over fuel.”

Yet it’s not all about profit for Aramco. The 2030 plan envisions the company’s chemicals buildup as a catalyst to spur manufacturing that will create jobs beyond oil. Such investments will “foster the growth” of local industries, it said in its 2015 annual report.